James P. Byrnes, of the Department of Psychological Studies in Education of Temple University, is a developmental psychologist with a primary interest in the factors predictive of academic achievement, as well as in the developmental trajectory of publishing expertise in psychology faculty. He can be contacted at jpbyrnes@temple.edu.

When considering a faculty member for tenure, decision-makers typically have some unofficial numerical standard for the candidate’s publishing history. But this and other assumed benchmarks seem to be passed around mostly by word of mouth. Those decision-makers also assume that each cohort of newly minted faculty members publishes more articles before earning tenure compared with previous cohorts.

In the mid-1990s, I was serving as associate dean for faculty. One of my responsibilities was to shepherd untenured faculty through the tenure process. Colleagues within my institution and around the United States told me that, whereas untenured people used to be required to publish two articles per year to get tenure, they now need to publish four. Having reviewed a number of promotion and tenure cases for both my own institution and others, and having already published several articles on productivity, I knew this assertion was probably untrue. But I needed proof. So, I conducted a study in the mid-2000s to see how often untenured faculty actually published.

Because I expected the findings to be challenged or dismissed if they did not reveal an increasing rate of publishing over time, I wanted to make as strong a case as possible. First, I focused on nearly 300 faculty who obtained tenure in the top 25 psychology programs (as rated by U.S. News and World Report). The data would be harder to dismiss if they showed no increases in published articles with each successive decade in these individuals than if I included faculty from lower-ranked programs.

Second, I focused only on developmental, social, and cognitive psychologists; published studies of productivity showed that faculty in these programs tend to publish at a higher rate than clinical, counseling, school, and educational psychologists. After locating the faculty via websites and examining their CVs or looking up their publications on PsycINFO, I found that the rate of publishing was nearly identical regardless of decade: roughly 1.58 articles per year. I also found that faculty whose records placed them below the 25th percentile published less than one article per year.

When I submitted the study to Psychological Science in 2007, the editor and reviewers were so surprised that they asked me to do several supplemental analyses, such as considering the impact factors of the journals and publication of chapters. None of the alternative explanations could account for the lack of increases. After the article was published, I received many emails from untenured folks thanking me, reporting that their senior faculty were telling them the norms had changed when my data showed they had not.

Fast forward to 2023: When I recently discussed several tenure cases and reviewed cases for untenured faculty at other institutions, I discovered that the “norms have increased” meme had reemerged. I initially tried to ignore this claim or dissuade others, based on my earlier research and other published studies. But I began to wonder whether things might have indeed changed.

First, as reported in gradPsych, a now defunct publication for graduate students, the economic collapse of 2008 caused a number of institutions to receive decreased revenue from state budgets, resulting in several years of hiring freezes. Second, the droves of psychology faculty hired in the 1970s did not retire in the 2000s and 2010s as expected, prompting concerns that the demand for academic jobs in psychology may exceed supply. In addition, other gradPsych articles reported that many institutions replaced tenured positions with contingent positions. Together, budget cuts and loss of tenure-line positions would severely restrict the supply of open positions, and the resulting spike in competition would leave only the top performers landing jobs.

Finally, the number of recent psychology PhDs seeking postdoctoral fellowships—once a rarity—started to increase in the early 2000s. In the sample I analyzed for my follow-up study, I found that 73% of the faculty had 1–5 years of postdoctoral experience, suggesting the practice is now the standard. Without teaching demands, these postdoctoral fellows presumably have extra time to publish. One might expect that these individuals would have published more in their first 7 years after completing graduate school than previous recent graduates who had not completed postdocs.

The methodology for the follow-up study consisted of looking at the publishing rates of faculty who earned their degrees between 2000 and 2009 (Decade 1) or between 2010 and 2016 (Decade 2) and who now hold positions at the same top 25 departments that I examined in my 2007 paper. Because the number of positions was halved since my earlier paper, I added faculty from another 11 schools that were rated a notch below the top 25 in the U.S. News rankings to bring the sample size to 300. I once again relied on their CVs and PsycINFO for publication data.

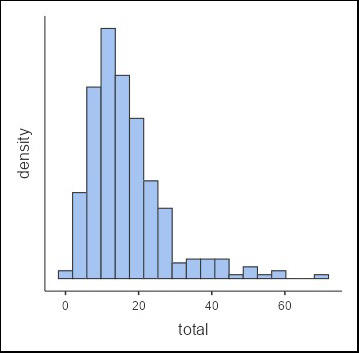

Whereas faculty in the 2007 article published at a rate of 1.58 articles per year (11 total), the more recent cohorts published at a rate of 2.43 articles per year (17 total). So, yes, the more recent cohorts are publishing more, amounting to about one more article per year (or 6 more total). However, the distribution was highly skewed: Most centered on close to two articles per year, but a few (11%) published four or more articles per year (see Figure 1).

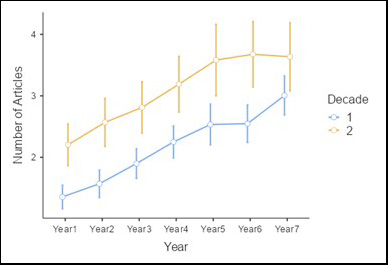

Relatedly, I found no statistically significant differences between developmental (2.48 articles per year), cognitive (2.29 articles per year), and social psychologists (2.56 articles per year). I also found no significant difference between faculty who hold positions in the top 25 programs and those in the next tier. There was a significant difference between those who earned their degrees in the 2000s (Decade 1) and those who earned their degrees after 2010. However, a growth curve analysis showed that the rate of change over the 7 years analyzed did not differ between the two groups. The Decade 2 group had more publications before getting hired and this gap was sustained over the subsequent years (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 also shows that the publishing rate increased each year for the first 5 years, as faculty gained publishing expertise, and then plateaued. (Note: This appears to hold more for Decade 2 than for Decade 1.) How (or why) did the more recent cohorts publish a little more than prior cohorts?

First, as noted, 73% of the faculty who posted their CVs completed postdoctoral fellowships, often with a neuroscientific focus. Second, colleagues and mentors may be telling these faculty that they need to publish more than two articles per year, leading them to find creative ways to publish six more articles in total than prior cohorts. Many created collaborative teams with untenured faculty at other institutions or published short (1–2 page) commentaries or neuroscience pieces in addition to regular length articles. Finally, the competition for jobs is much stronger than in the past: Whereas 151 faculty in the present sample obtained a tenured position between 2000 and 2006, only 75 obtained a tenured position between 2010 and 2016, suggesting open positions fell by half. This may advantage those unusual individuals who published a great deal in their predoctoral and subsequent years.

These findings lead to a question: What should the standards be for untenured faculty who work at institutions ranked lower than those examined here, and who are not fortunate enough to have access to untenured collaborators, a cadre of talented and motivated graduate students, or fMRI equipment? Given the data here, it seems like the standard of two articles per year still applies.

Feedback on this article? Email apsobserver@psychologicalscience.org or login to comment.