Help students plan their future • Promote job success broadly • Coursework • New training opportunities

“We want people with a PhD out there writing for the New York Times or other public media, explaining issues around Ozempic or a new health claim. Really analyzing the data and looking at it and synthesizing it so that your average person could understand and say, ‘Oh, wait a minute, maybe there is a reason I shouldn’t take this drug or follow this recommendation.’”

Patricia Labosky, Program Leader, Office of Strategic Coordination, National Institutes of Health (NIH)

As someone who studies habits, I think a lot about why people get stuck repeating behaviors that aren’t ideal. Most of us have been mired in our own behavior patterns at some point. Even if it is clear that change is needed, we persist in doing what we’ve always done. And it’s easy to see graduate training in psychology through this lens.

Many PhD programs do a great job of equipping students for academic positions, especially tenure-track jobs at R1 institutions. But as I’ve noted in prior columns, this training model doesn’t match job-market realities. The majority of psychology PhDs get jobs in tech industries, human resources, science writing, teaching, law, or administration. Clinical psychologists are especially likely to work outside of academia, but this is also true for other students. The majority do not become tenure-track academics.

A single-track focus on training students for academic positions also doesn’t recognize the diversity among our students. They are highly selected for their intellectual prowess, but they still have different interests and talents. Additionally, the focus on academic jobs overlooks the varied ways students contribute to our society’s economic growth and well-being. Many students will thrive most happily—and make the most important contributions—in jobs outside of academia.

Students know that change is needed. For example, a student in a recent survey requested that we “model more career pathways than R1 academic jobs. It’s not realistic that all … graduates will get those positions … [and] our professors … don’t take steps to educate themselves or connect us with role models pursuing other career paths.”

How can programs better accommodate diverse careers? Changing organizational habits is in many ways similar to changing personal ones. That is, start by identifying specific new actions that support diverse career goals. Consulting graduate student interest assessments is a good way to identify gaps in training. Then, make change easier for faculty by creating program structures such as diverse coursework, job placement reports that feature academic and nonacademic positions, and internships that promote basic and applied training.

I had the opportunity to talk with several experts who successfully innovated graduate training for diverse careers. The recommendations below draw heavily on their advice.

Help students plan their future

Patricia Labosky, administrator of the NIH program, Broadening Experiences in Scientific Training, was clear about the benefits of understanding career options early on. She tells students, “Never follow my career path. I was a tenured professor for 15 years. I ran my own lab and loved it, but then my goals changed, and I came to NIH. Mine is a round-about career path and not the ideal route to my current position. Instead, recognize early what you might want to do and not want to do, and go forward with that in mind.”

A great way for students to identify potential career paths is a self-assessment of skills, interests, and values. The American Association for the Advancement of Science and partners have a helpful independent development plan (https://myidp.sciencecareers.org/).

Although this exercise can be really useful, students may need some encouragement to complete it. Even when required by programs, the self-assessment was only completed by about one third of students.

Of the students who did complete a self-assessment, the majority were reluctant to discuss their career plans with their mentors. I’ve heard this hesitancy from students when I visited graduate programs and met with them separately from faculty. Students report that their advisors wouldn’t understand their desire to get a teaching position or a nonacademic job in human resources or tech.

Ideally, self-assessments would clarify training goals for advisors and for students. After all, it’s difficult for students to get their desired training without sharing career goals with faculty—failing to do so perpetuates mismatches between training and careers. Early assessment is important given estimates that over 80% of health science PhDs end up staying in the career stream of their first job.

Not everyone has this reluctance to share their career plans. As Patricia explained, “I think the current trainees are a little fed up, and they’re just telling people what they want to do. I ran into quite a few of those. They said, ‘I’m going to do this [nonacademic career], but I will also do my best, and I will do a great PhD. And you’ll [their advisor] get a bunch of papers out.’ So instead of hiding their career ambitions and fears, they’re being honest and direct.” I predict that these students will be especially successful.

Promote job success broadly

Academic careers can seem like the only ones with value when programs advertise placement of students in R1 academic positions over nonacademic placements. As one student noted in a survey of clinical training programs, “It is extraordinarily frustrating that faculty do not seem to value clinical work, that only alum who are now prestigious researchers are ever mentioned … it’s like those who do any amount of clinical work failed.”

But even NIH training grant criteria now recognize that successful placements occur in a variety of research-related positions. Officially, “Such work may take place in academic, government, non-profit, or commercial settings, including biotechnology or pharmaceutical companies.” As Patricia emphasized, “With the BEST [Broadening Experiences in Scientific Training] awards, the NIH put money into saying that it’s OK if you’re not a professor [or] if you go into science writing or [something else].” But she noted, “Faculty are hesitant to put on their website where all their students went. They look at it as, ‘Oh, it’s going to be seen as a failure.’”

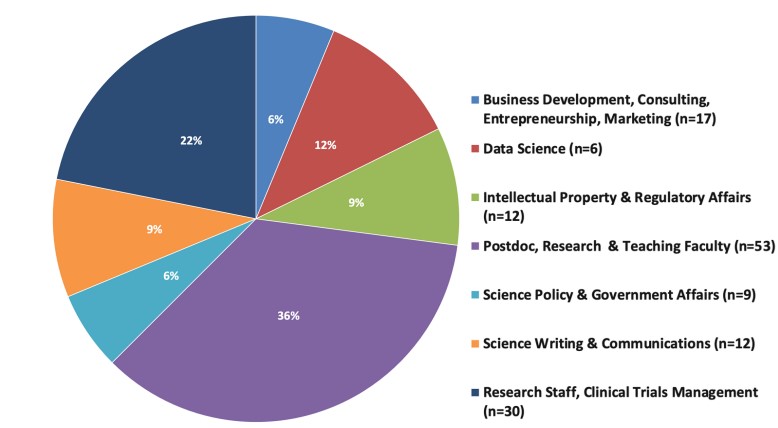

Yet some programs are already doing this. For example, the University of California, Irvine reports their STEM alumni jobs in this way:

Everyone benefits from this broad career recognition. Prospective students learn that they will be supported by a graduate program regardless of their own career choices. Former students can benefit from the feeling that their work is being recognized.

Coursework

I had the chance to talk about coursework with APS Fellow Holly Taylor, APS Fellow and Professor of Psychology and Mechanical Engineering at Tufts University. Her classes are designed for both applied and basic research careers. She noted, “When I was in graduate school, people didn’t really talk about nonacademic careers. I went on to an academic career, but a lot of my fellow students would talk about wanting to go into industry and almost lament the lack of courses on applied work.”

But, in Holly’s view, “It’s not the courses that differ between our students who successfully move into industry and those who don’t. It’s the framing of ideas within the courses. You can frame things theoretically, which is fine. People need to understand the theory, and they need to be able to think about how the theory informs their research. And that’s true from both applied and basic research approaches. But you can also give examples of why a problem matters in the real-world space.”

Holly continued: “Give an example of a student studying visual search and auditory interruptions. This is a basic research question. What happens if you have interference in the perceptual processing streams? The application is you’re driving a car, and you need to pay attention to the road, but, at the same time, you might have an auditory interruption of an emergency vehicle and need to localize where that vehicle is coming from and what you need to do. This is the framing question: How can you frame what you’ve done in a way that has utility for whatever job you’re moving into?”

I asked Holly if she would encourage such a student to take courses in relevant domains, say transportation safety or risk assessment. She answered, “I wouldn’t actually. It’s a content-based versus a process-based approach. And I am a little bit stronger on the process side.”

She went on to say, “That’s the second part of my advice. We often think about what literature people need to read, what theories they need to know, what researchers they need to be aware of. All are super important. But I would add: What skills does a graduate student need to ramp up quickly on any project? Students need to learn how to extract the skills acquired in a particular domain and apply these more broadly. Practice doing that. They learn about basic psychological processes, how to interpret research, and the process of application.”

Finally, she said, “The last thing I’ll end with is that statistics and research methods are core critical skills for students in all careers.”

Other programs, by contrast, offer specific skills-training courses designed to reduce knowledge barriers for students taking jobs outside of academia. For example, the STEM program at the University of California, Irvine offers classes in business concepts and science entrepreneurship, project management, medical writing, and science policy and advocacy. The idea is to train specific skills useful in any job sector.

New training opportunities

NIH’s BEST program was designed to increase students’ understanding and faculty acceptance of diverse careers for health science PhDs. I asked Patricia what parts of the program were most successful.

Internships. Experiential learning, especially internships, was a major focus of BEST programs. “Everybody leaned into internships at first, thinking that they were going to be the best thing. But they weren’t necessarily. Some faculty weren’t enthusiastic about trainees going off on internships. They were more accepting if the trainee went into an industry where they brought something back to the lab—a technique, an approach, or a collaboration.”

She noted the complexities of setting up internships. “It’s a really tricky thing about internships. Full time versus part time? Salaried or not? Insurance? The trainees have to sign all these nondisclosure agreements, and then they can’t talk about what they did? So, instead, short-term, part-time experiences were often preferred over formal internships.”

But when successful, internships can give students a direction to their studies. Patricia noted, “When internships worked, students got more enthusiastic about finishing their research projects, getting out, and finding another position. Once they saw there was something positive out there for them, their attitude changed. Instead of [saying], ‘Oh, I guess I’ve got to finish this paper or project,’ they instead felt, ‘I am going to finish my degree so that I can go get that job.’”

Internships can be a successful way of launching students into their desired careers. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill assessed the effects of internships as part of the BEST program. UNC-Chapel Hill interns were nearly three times more likely to get a first job that matched their (pre-internship) career interests than noninterns. Faculty also saw benefits, as some students brought instrumentation and other skills from their internships back to the lab. And internships could have a positive knock-on effect on lab culture. As one advisor noted, “Other people in the lab saw that I put their careers first … and they were pleased to see that I allowed people to take this time off to pursue … their career opportunities rather than saying, ‘No, you’ve got to get your papers out.’ So, I think it sent a positive message to the rest of the lab that I’m very supportive of their careers.”

Take advantage of local strengths. Successful BEST training programs took advantage of local industries. As Patricia noted, “Some folks ended up doing site visit kinds of trips to local industries with a few trainees. They would go to sites and learn about what the people do, what the company does. A lot of this is about where you are across the U.S. and what you have in your backyard that you can visit. For example, Rutgers has a ton of nearby biotech, so that made it easy. For UNC-Chapel Hill, Research Triangle Park has lots of small companies that love to host trainees to come and see what they do.”

Career panels. Finally, Patricia mentioned career panels, which have become a standard feature of APS conventions. “Career panels kind of get a bad rap because they’re easy to do and people get bored with them. But I always think it’s good to hear people’s stories, why they ended up doing what they’re doing. And I think it makes a big difference if you have former trainees, people who were at your institution, come back to talk. They got a degree from this department, and they’re going off and doing or not doing the academic path.”

In summary, Patricia concluded, “I think hitting trainees with data about the fact that not everybody with a PhD has to be a professor makes a big difference.”

Feedback on this article? Email apsobserver@psychologicalscience.org or login to comment.

Resources for program development

Brandt, P. D., Whittington, D., Wood, K. D., Holmquist, C., Nogueira, A. T., Gaines, C. H., Brennwald, P. J., & Layton, R. L. (2023). Development and assessment of a sustainable PhD internship program supporting diverse biomedical career outcomes. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.13.548912

Gee, D. G., DeYoung, K. A., McLaughlin, K. A., Tillman, R. M., Barch, D. M., Forbes, E. E., Krueger, R. F., Strauman, T. J., Weiericj, M. R., & Shackman, A. J. (2022). Training the next generation of clinical psychological scientists: A data-driven call to action. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 18, 43–70. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-081219-092500

Lenzi, R. N., Korn, S. J., Wallace, M., Desmond, N. L., & Labosky, P. A. (2020). The NIH “BEST” programs: Institutional programs, the program evaluation, and early data. The FASEB Journal, 34(3), 3570–3582. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.201902064